A greener blue revolution - Part 1

The aquaculture industry must continue in its quest to become more sustainable, with greater use of seaweeds in aquafeeds and production of herbivorous fish among two of the most promising avenues to achieve this.

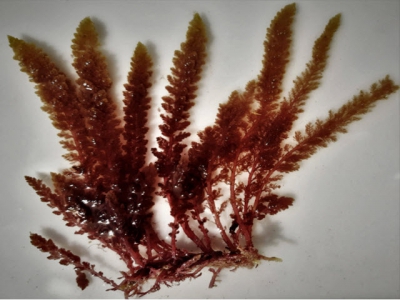

A gametophyte of Asparagopsis taxiformis. Photo: Valentin Thepot

It’s not good enough to accept the well-worn cliches about the benefits of aquaculture. There are still huge improvements to be made and it’s important for researchers to help the industry push the boundaries – for example, by revealing the benefits of seaweed in aquafeeds and the unmet potential of numerous species of herbivorous fish.

What inspired me to take up aquaculture

I was born in Penn ar Bed (Brittany, France) and spent most of my childhood between the family dairy farm inland and the sea, once we moved to the coast. I have been in love with farming on land and with the ocean since I can remember but I only put the two together when I arrived in Australia in 2008 to complete my BSc. I then had my first aquaculture lecture with Dr Nicholas Paul at James Cook University (Townsville, Queensland) and I knew straight away that this was for me.

Wouldn’t changing the species of fish we grow be easier than trying to change the diet a fish has been accustomed to for 10-20 million years? Can we farm fish down the food chain in the sea the same way we farm herbivorous livestock on land?

So, after my first semester at JCU, I changed my major from marine science to aquaculture. During my degree, I volunteered at, and then worked in, a commercial barramundi (Lates calcarifer) hatchery at JCU for three years and realised during that time that, although farming practices had significantly improved since the early days of aquaculture, there was still a lot of room for improvement (fish growth rates, survival and environmental footprint to name a few). This curiosity and desire to continuously improve aquaculture practices and know-how led me to commercially-driven research and, ultimately, to taking up a PhD at the University of the Sunshine Coast (USC) with the Seaweed Research Group.

There is no doubt in my mind that aquaculture can help with food security. It is the fastest growing food producing industry and 50 percent of the fish we consume are now farmed. That is great, but we need to make sure this does not come at a cost. There are two main limitations in the way we grow fish at the moment: 1) reliance on wild-sourced ingredients such as fishmeal and fish oil to farm carnivorous fish and 2) disease outbreaks costing the industry over $6 billion a year (Stentiford et al., 2017). A lot of effort is and has been spent on replacing wild-caught ingredients in the diet of carnivorous fish, with some very promising solutions for the future (Hua et al., 2019). But wouldn’t changing the species of fish we grow be easier than trying to change the diet a fish has been accustomed to for 10-20 million years? Can we farm fish down the food chain in the sea the same way we farm herbivorous livestock on land?

Room for improvement

Although aquaculture is the fastest growing food-producing sector, disease outbreaks are a clear limiting factor to its sustainable development. Putting the financial impact of disease outbreaks aside, about one out of ten fish grown in aquaculture is lost due to disease and will not make it to the consumer’s plate. Additionally, the current methods for treating and preventing disease and parasite outbreaks tend to revolve around veterinary drugs, including antibiotics and other chemotherapeutics. The use of such treatments can have detrimental effects on the environment, the treated fish and – ultimately – it may also have direct or indirect human health implications (Okocha et al., 2018). Although aquaculture uses very small amounts of antibiotics compared to other primary industries, antibiotic resistance was described by the World Health Organisation, during the Covid-19 pandemic, as “one of the biggest threats to global health, food security, and development today” (WHO, 31/07/2020). I have no doubt that antibiotics and other chemotherapeutics serve as an important tool to maintain the welfare of farmed fish, but there is equally no doubt that we need to find alternatives and wean the sector off them.

The fact that antibiotic resistance already claims 700,000 lives each year and has been forecast to kill as many people as cancer by 2050 (10 million annually) acted as my alarm bell. We need to act now and find alternatives to treat and prevent sick fish. This is why the first thing I did during my PhD was to look at what natural alternatives are used to treat/prevent fish diseases in aquaculture.

How seaweed can help

I read multiple scientific publications on probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, immunostimulants (eg β-glucans), plants as dietary supplements that could bolster the immune system of fish and ultimately make the fish more resistant to pathogens, reducing and at times eliminating the need to treat fish with traditional chemotherapeutics. In that literature search, seaweed was an ingredient that kept coming back with some very promising results. To confirm my hunch, I decided to compile all the immune (and growth) related data from all 142 published studies which investigated the use of seaweed as a fish immunostimulant. This exercise resulted in a spreadsheet with just under 20,000 entries. I then re-analysed those data and published my work as a meta-analysis review in Reviews in Aquaculture (Thépot et al., 2021a).

In this review, I found that dietary seaweed supplements significantly improved fish immune responses and ultimately made them more resistant to disease when exposed to a pathogen challenge. This review also highlighted that most of the studies investigating the use of seaweed as an immunostimulant for fish only focused on one seaweed species, with the maximum of three seaweed species being tested in a single trial. Considering there are >11,000 species of seaweed globally, with a range of different bioactive properties, I was surprised to have only 34 different seaweed species represented in the 142 reviewed studies. In addition, only two studies out of 142 looked at the effects of seaweed dietary supplements in marine herbivorous fish – species that would naturally encounter and eat seaweed in the wild.

Có thể bạn quan tâm

Phần mềm

Phối trộn thức ăn chăn nuôi

Pha dung dịch thủy canh

Định mức cho tôm ăn

Phối trộn phân bón NPK

Xác định tỷ lệ tôm sống

Chuyển đổi đơn vị phân bón

Xác định công suất sục khí

Chuyển đổi đơn vị tôm

Tính diện tích nhà kính

Tính thể tích ao hồ

A greener blue revolution - Part 2

A greener blue revolution - Part 2  Preventing substandard shrimp seed trading

Preventing substandard shrimp seed trading