The basics of hands-on dairy training

Your Future Dairy Training offers aspiring farmers hands-on and practical training.

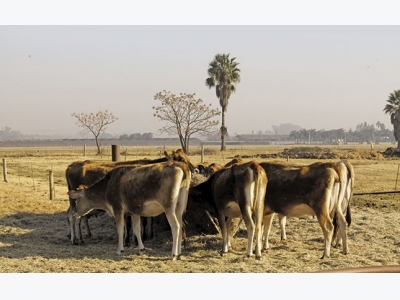

Jersey cows at the hay ring on Kiewietsvlei farm north of Pretoria. Photo: Nan Smith

Transformation in SA’s dairy sector involves dairy training and the transfer of knowledge, as managing a dairy herd, big or small, requires expertise.

Reports of animal deaths on farms, including some owned by high-profile public servants, are in all likelihood a testimony to ignorance and a lack 0f practical dairy training more than anything else.

In February, the Mail & Guardian uncovered a gruesome tale involving a high-cost dairy project in the Free State, where animals were said to be dying daily and carcasses dumped in a ditch.

Dairy cows cannot simply be turned out and left on their own. They will not survive. It is imperative that government bears this in mind when purchasing expensive, high-producing animals for state-funded projects. Ignorance can no longer be accepted as an excuse for business failure and outright cruelty to animals as there are now a number of facilities where aspirant farmers can be trained. Your Future Dairy Training at Kiewietsvlei farm north of Pretoria is one such centre.

Experienced stockwoman Karin Pretorius and her dedicated three-man team offer practical training of a high standard in general animal husbandry and management, with specific emphasis on dairy cattle and parlour management.

“People who need this kind of training include developing farmers and students, or farm workers looking to upgrade their skills,” says Karin, who has mentored students for the past nine years.

Foundation phase

“Nobody can milk cows if they don’t know anything about it. Mistakes can be crippling,” says Karin. “And once they have the basics, keeping up to date is vital.”

At Kiewietsvlei, where Karin’s Jersey herd and training facility are based, she offers a five-day course in basic livestock handling for beginners, as well as an advanced course.

“We’ve had people come here without any idea of how to handle large animals,” she says.

“Subsidies may make it possible for developing farmers to buy a few in-calf dairy heifers, which is really small-scale and subsistence farming. These farmers sell excess milk once their animals have calved, which can make a difference to food security in communities.”

This is in line with the sentiments of Mike Mlengana, chairperson of African Farmers’ Association of South Africa, who said recently that alleviating hunger in communities could be achieved by small-scale farmers.

“Teaching people how to get the most out of small units suits my system because I like working on a smaller scale and I have done well out of it,” Karin explains.

She is currently in the process of getting AgriSeta (Agricultural Sector Education Training Authority) accreditation, which she hopes will make it easier for potential students to access funding.

“People phone me and want to do my courses but don’t have the money to pay for them, or have a false expectation that the courses will be free.”

On her 14ha farm, Karin’s 10-point parlour and small TMR Jersey dairy herd is an ideal training ground for first-time dairymen and women, because it lacks the ‘intimidation’ factor of large herds.

It also allows Karin to supervise students in a friendly environment without losing the essential principles of dairy herd management.

Getting the basics rights

Team member Phineas Mamadi, who has worked at Kiewietsvlei for 10 years, puts his finger on a problem in livestock management when he says: “You can learn to read and write, you can learn from books, but the real learning comes from experience, from working with the animals.”

In discussion, Phineas and his colleagues and fellow stockmen, Piet Makhubela and Daniel Mogorosi, say that government-funded start-up dairy enterprises have failed because herd managers do not know the basics.

The trio questions the wisdom of allowing people to farm dairy without some grasp of the principles and procedures involved, and agree that the solution can be at least partially found in providing relevant practical training.

“Many students have come here with book learning, but when it comes to practice they know nothing,” says Phineas.

Practical experience crucial in dairy training

TUT (Tshwane University of Technology) animal production student Tsakane Chabalala, who worked at Kiewietsvlei during her compulsory practical year as part of her diploma in animal production, says that the team taught her “everything”.

Tsakane grew up in nearby Hammanskraal with a grandfather who farmed cattle, pigs, goats and chickens on a small-scale, and explains that she gained invaluable experience during her practical year on Kiewietsvlei.

Looking back, she says that the sheer volume of the work shocked her at first, and at times she wept from sheer exhaustion, but she learnt about dairy farming.

“Sometimes students have no idea of the work involved,” says Karin. “It may be that when they come on courses such as the ones I offer, they learn that they are not cut out to do this work.”

Universities, technikons and agricultural colleges at tertiary level often have difficulty in providing students with the necessary practical segment of their education.

Educational institutions need assistance from the private sector to ensure that students receive this and farmers like Karin have in the past received no financial compensation for their contribution. In fact, she points out, they must often pay students for what is effectively their field study year.

Without the opportunity provided by facilities such as Karin’s, most students would find it impossible to gain practical skills. Commercial dairy farmers running large herds with skilled staff already in place do not have the time to train students.

In 2004 in the Eastern Cape, under the guidance of South African dairy guru, consultant Jeff Every, dairy farmers were involved in setting up transformation dairies, and gave of their money and time to developing farmers.

But these dairies are different – they are large-scale ventures with upwards of 600 cows in milk, and it would be foolish to put untrained personnel in place. Here managers must be skilled dairymen and then receive training in people and financial management.

Dairy training in the working day

In a small system such as the one at Your Future Dairy Training, students are subjected to the sometimes harsh realities of the working dairy day.

They rise before dawn to milk, learn how to wash milking machines, pipelines and tanks after every milking, disinfect the plant, and wash down the parlour.

Vacuum pumps, the importance of the correct pressure, and the cooling and agitating of milk are all components of parlour management. Mistakes and ignorance in the parlour can mean mastitis and milk loss – and every litre is precious, explains Karin.

There are three basic training grounds: the parlour and its associated machinery, the dairy cattle in various groups, and the feeding regime, whether the herd is pasture-based or on total mixed rations (TMR).

“Here, students can learn how to take care of the cow, basic ration balancing and the inclusion of minerals and roughage. We have a TMR system because we don’t have the land to run a pasture-based system, but there are lands we use for pasture practical training.”

The training includes: rearing dairy cattle from calves to point-of-calf heifers, calving, care of milking cows, dry cows and steam-ups, monitoring for various diseases, dipping, dosing, various medicines and their applications, and vaccination programmes.

The right niche

Karin says that small-scale dairy operations can survive and even thrive if they are close to centres of demand where niche markets exist. Direct milk sales from farms to areas such as Hammanskraal offer the opportunity to earn extra cents on a litre.

Karin’s milk goes to a small dairy processor in Hammanskraal who pasteurises it and then sells it in the township and to local shops. Often, raw milk is preferred because it can be used to produce maas, the popular fermented milk.

Hygiene standards must be excellent if milk is to be supplied raw (unpasteurised) with low somatic cell counts. Cows must be tested for TB and brucellosis. Tsakane maintains that there is a definite advantage to entering the workplace with the right academic background coupled with experience. Training such as that offered at Kiewietsvlei assists in bridging the gap and passing on the confidence that accompanies skills acquisition.

Related news

Tools

Phối trộn thức ăn chăn nuôi

Pha dung dịch thủy canh

Định mức cho tôm ăn

Phối trộn phân bón NPK

Xác định tỷ lệ tôm sống

Chuyển đổi đơn vị phân bón

Xác định công suất sục khí

Chuyển đổi đơn vị tôm

Tính diện tích nhà kính

Tính thể tích ao

3 diseases spread by wildlife

3 diseases spread by wildlife  The smallest part of the ruminant diet

The smallest part of the ruminant diet